Digging deeper into Google’s anti-censor stance-The Atlantic

March 31, 2010

An Interview with David Drummond of Google

James Fallows

The Atlantic: March 23, 2010

http://www.theatlantic.com/science/archive/2010/03/an-interview-with-david-drummond-of-google/37896/

Just now I spoke on the phone with David Drummond, Google’s chief legal officer and author of yesterday’s Official Google Blog post about the company’s new policies in China.

Highlights from the discussion below. I was typing this down in real time, so it may be 98 rather than 100 percent faithful to what he actually said. The entire discussion was on the record.

I began by asking what was non-obvious about the development — an aspect of the story known on the inside that had not been captured in the public reports:

It may not be quite obvious that this is not really a “shutdown” of either our operations in China or of our mainland China-focused web site. We have moved the physical location of it [to Hong Kong], and the virtual location. The experience we are trying to offer to Chinese users is like the one on Google.cn, but done without the censorship on our part.

[Would this make any difference to users in mainland China, whose search results are still going to be “filtered” by the Great Firewall?] There is a difference in that we are censoring nothing. The Firewall can block access to certain kinds of search results regardless of how you get to them. They are treating Google.com.hk – treating it like Google.com [that is, as a foreign source that is screened by the Firewall]….

People tended to see this as an all or nothing kind of battle between us and the Chinese government, and that based on what we said, we were either going to pull out of China entirely, or else say, Never Mind! From the beginning our view had been, we would like to stay in China and have an operation there and serve the market there, and serve it as locally as we can. We’re just not willing to censor the search results any more.

I think there has been some grumbling or people questioning whether this is some kind of “deal” with the Chinese government. That’s not the case. We had conversations with the government. Would they be willing to lift the search- censorship requirements, in terms of the substance and even more the lack of transparency? They made it clear that the self-censorship policy as it is now practiced was not going to change.

I then asked Drummond about something that has always puzzled me. If the original occasion for the shift of policy was (as generally reported) a hacking episode, why did it lead to a change in the censorship policy? What’s the logical connection? He explained the reasoning in a way I hadn’t seen before.

The initial premise, that it all started from a hacking episode, is not quite right. We did have a hacking incident. Most hacking incidents that you see are freelancers — maybe government sponsored, maybe not. They are out there trying to steal intellectual property, make some money. Or they might just be hackers who want to damage something for whatever reason. That’s a fact of life that internet companies deal with all the time.

This attack, which was from China, was different. It was almost singularly focused on getting into Gmail accounts specifically of human rights activists, inside China or outside. They tried to do that through Google systems that thwarted them. On top of that, there were separate attacks, many of them, on individual Gmail users who were political activists inside and outside China. There were political aspects to these hacking attacks that were quite unusual.

That was distasteful to us. It seemed to us that this was all part of an overall system bent on suppressing expression, whether it was by controlling internet search results or trying to surveil activists. It is all part of the same repressive program, from our point of view. We felt that we were being part of that.

That was the direct connection with the hacking incident. It wasn’t in isolation. Since the Beijing Olympics, our experience in China has gotten worse. Although we have gained market share, it has become more and more difficult for us to operate there. Particularly when it comes to censorship. We have had to censor more. More and more pressure has been put on us. It has gotten appreciably worse — and not just for us, for other internet companies too.

So we increasingly came to feel that the original premise of our entry into China was being undermined. We thought when we went in that we could help to open the country and things could get better by our being there. Things seemed to be getting worse.

And what happens now?

We don’t know what to expect. We have done what we have done. We are fully complying with Chinese law. We’re not operating our search engine within the Firewall any more. We will continue to talk with them about how to operate our other services.

We originally went to them with a request [for a change in the filtering rules]. They made it clear that the self-censorship system was the law there and it wasn’t going to change. We’ll keep talking with them about everything else.

Finally I asked why Google had not stopped censoring its results more quickly, at the time it announced its changed policy on January 12 or soon afterwards. Was it mainly concerned about legal jeopardy for its employees in China? Is it concerned about them now?

We certainly hope they are not at risk. They had nothing to do with these decisions, and what we are doing is within Chinese law. So there should not be any reason for them to be at risk.

We did not stop censoring immediately because we wanted to engage with the government about how and whether we could keep operating. And if self-censorship is the law, we weren’t interested in blatantly violating the Chinese law within the Firewall –much as we disagree with that law. As I said in the blog post, it was hard to sort this through. But we needed a way to continue that was consistent with our principles.

James Fallows is a National Correspondent for The Atlantic. A 25-year veteran of the magazine and former speechwriter for Jimmy Carter, he is also an instrument-rated pilot and a onetime program designer at Microsoft.

March 31, 2010 at 8:09

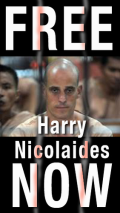

Does Google still perform as a censor for other governments, the Thai especially?

I think they do.

Is Google still the renderer of ‘Soylent Green’… packaging and marketing its customers as its product?

You bet it is!

August 12, 2010 at 3:22

Would I be wrong to assume that if the Chinese government chooses not to renew Google’s licence, their next step would be to black list Google.com.hk in their firewall.